Intro

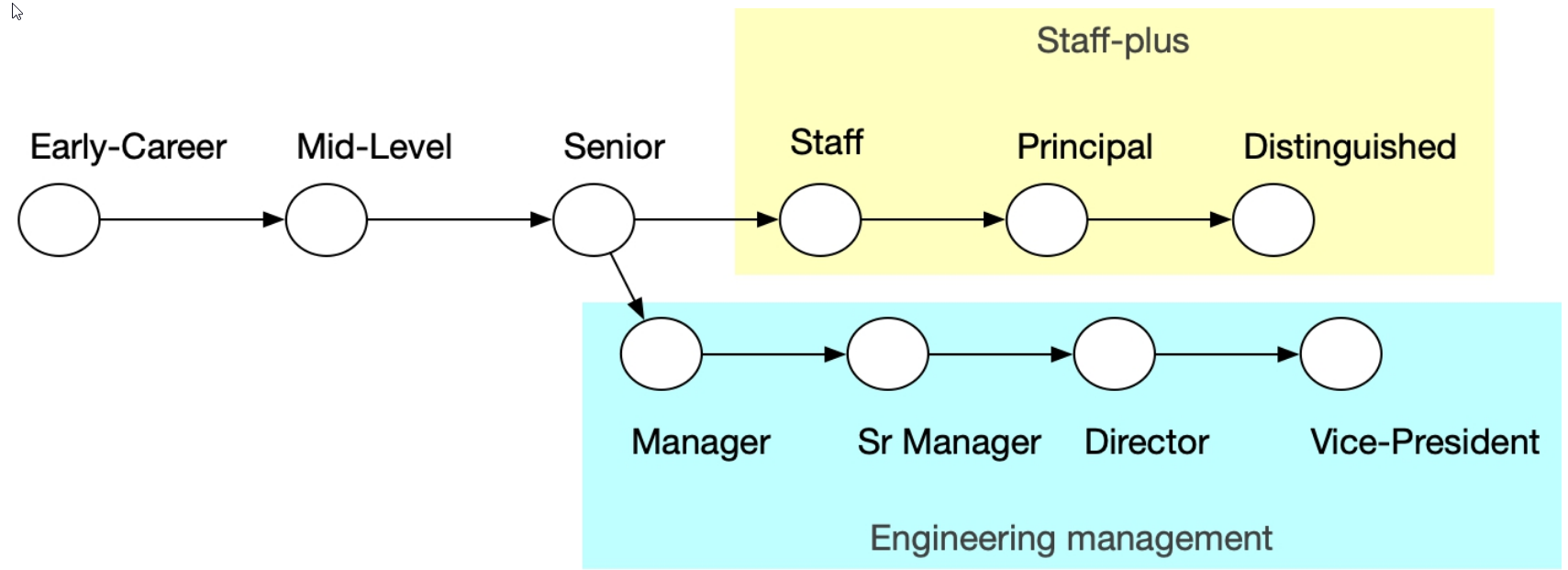

Software engineers usually reach the Senior level within 5-8 years in the tech industry. At this stage, further promotions are not mandatory and are more of an exception than an expectation. At this point, engineers often have the option to transition into engineering management (see Manager's Path).

However, for those who wish to advance their careers without shifting to engineering management, many companies offer a two-track career path. The first track is engineering management, while the second is technical leadership, with roles like Staff Engineer and Principal Engineer.

Career tracks splitting into staff-plus leadership vs engineering management

The book identifies four distinct staff-plus engineer archetypes across companies:

| Archetype | Description | Primary Responsibilities | Operating Environment | Common in Company Size/Type | Key Skills or Traits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tech Lead | Leads a team or cluster of teams in approach and execution. | Scoping tasks, team coordination, technical vision. | Agile, team-centric companies. | Varies, often in medium to large companies. | Project management, technical expertise. |

| Architect | Responsible for a specific technical domain. | System design, business and user need understanding. | Companies with complex or coupled codebases. | Large companies, those addressing technical debt. | In-depth technical knowledge, foresight. |

| Solver | Tackles complex, critical problems. | Problem-solving, working on organizational priorities. | Individual-centric planning companies. | Large, mature companies with technical debt. | Problem-solving, adaptability. |

| Right Hand | Operates akin to a senior leader without managerial duties. | Strategic problem resolution, delegation. | Senior leadership environments. | Very large organizations. | Strategic thinking, alignment with leadership. |

In order to understand which role is right for you - you have to stay engaged and know what kind of work energizes you. A tech lead or architect might work with the same people or problems for years, developing a tight sense of team and shared purpose. A solver or right hand type might bounce from fire to fire, only having transactional interactions with folks they're working with each week.

What do Staff Engineers actually do

"The role of a Staff-plus engineer depends a lot on what the team needs and also what the particular engineer's strengths are. ... usually their main focus is working on projects/efforts that have strategic value for the company while driving technical design and up-leveling their team." - Diana Pojar

There's a set of tasks that all archetypes will participate in - setting/editing technical direction, providing sponsorship and mentorship, injecting engineering context into org decisions, and being glue:

-

Setting Technical Direction:

- Serve as a part-time product manager with a focus on technology.

- Prioritize the real technological needs of the organization over personal interests in specific technologies.

-

Mentorship and Sponsorship:

- Influence the company's long-term growth by nurturing other engineers.

- Engage more in sponsorship than mentorship to maximize influence and support.

-

Providing Engineering Perspective:

- Offer valuable insights during critical, time-sensitive decision-making processes.

- Ensure that an engineering viewpoint is considered in important organizational decisions.

-

Exploration:

- Handle ambiguous, significant issues that fall outside the company's current systems.

- Build organizational trust to be tasked with exploration, accepting the risks of potential failure.

-

Being Glue (see Tanya Reilly's Being Glue):

- Undertake essential yet often unnoticed tasks to maintain team momentum and successful project delivery.

- Recognize the shift from frequent coding to facilitating broader project goals and team needs.

- This is an expected task when you're senior, but doing it too early can push people out of engineering

-

Coding and Contributions:

- Expect reduced time spent on direct software development compared to earlier career stages.

- Recognize frequent coding as a comfort zone indicator and a sign of potentially misplaced focus.

-

Pace and Feedback:

- Adapt to a slower feedback loop that extends over weeks, months, or even years, rather than immediate results.

Does the title even matter

If you're a senior engineer is it even worth it to invest time to become a staff engineer? Pursuing a staff-plus role offers several advantages::

- Informal gauges of seniority - Don't need to prove yourself as much, allowing you to focus on the core work

- Being in the room - able to provide input before implementation (when it's cheap to do so)

- Compensation - different than a senior engineer

- Access to interesting work - While the role can sometimes grant access to interesting work, a staff engineer can't just pursue interesting work out of personal interest as they should put the team or business first

Working on what matters

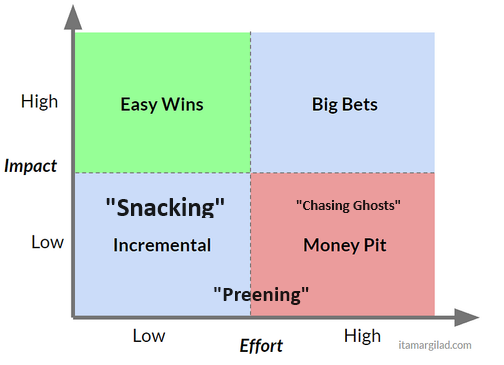

As individuals progress in their careers, the challenge becomes navigating the increasing expectations against the backdrop of a fulfilling life filled with family, hobbies, and personal growth. The essence of sustaining a long and successful career lies in pacing oneself, ensuring that as responsibilities grow, one doesn't sacrifice personal well-being for professional achievements. It's about consciously avoiding the pitfalls of busyness over productivity, vanity metrics over substance, and unattainable goals over realistic ones, focusing instead on work that truly matters both personally and to the organization.

Splitting technical staff-plus leadership and engineering management

There are also a few ways to get tripped up when looking to prioritize what to work on:

| Archetype | Description | How to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Snacking | Engaging in tasks that are easy and low-impact, offering a false sense of accomplishment. | Regularly evaluate the impact of your tasks and focus on those that align with organizational priorities. |

| Preening | Performing low-impact, high-visibility work, which can be misconstrued as impactful due to its visibility. | Seek out work that not only has visibility but also significantly contributes to the company's goals. |

| Chasing Ghosts | Pursuing high-effort, low-impact projects that may stem from a misunderstanding of company challenges. | Invest time in understanding the company's core challenges and resist the urge to initiate changes without thorough analysis. |

Writing Engineering Strategy

"I kind of think writing about engineering strategy is hard because good strategy is pretty boring, and it’s kind of boring to write about. Also I think when people hear “strategy” they think “innovation” " - Camille Fournier

Your company may call them RFCs or tech specs, but a good design doc describes a specific problem, surveys possible solutions, and explains the selected approach's details. Design docs should be grounded in specifics to prevent multiple different interpretations by engineers.

Writing an effective engineering strategy involves creating mundane yet essential documents that guide decision-making and align teams. The process of developing a strategy is straightforward and more effective than many realize. The book offers a few recommendations:

- Identify and Clarify the Problem - Begin with a clear statement of the problem, as it sets the stage for finding effective solutions. If solutions aren't clear, spend more time refining your understanding of the problem. When stuck, consult with others for fresh perspectives.

- Simplify the Design Document Template - Utilize the existing design document template of your company as a foundation. Avoid making the template overly complex, as this can deter people from writing design documents. Aim for a minimal template that highlights the most crucial sections, particularly for projects with significant risks.

- Collaborative Input, Individual Writing - Acknowledge that having all the relevant information to write the best design document is unlikely. Seek input from various stakeholders early in the process, but be cautious about turning this collaboration into a group writing effort. While it's important to incorporate a wide range of views, the actual writing should be a solo endeavor to ensure clarity.

- Aim for Quality, Not Perfection - Focus on writing a good and substantial document rather than waiting to achieve perfection. When providing feedback on others' designs, avoid the expectation that their work should match your highest standards. Especially in senior roles, encourage the production of quality work, rather than insisting on perfection in every design.

Synthesize the design docs into a strategy

After gathering five design docs, look for controversial decisions that came up in multiple designs (particularly those that were hard to agree on). An example from the book is deciding whether Redis is just a cache or if it's appropriate to use as durable storage. The idea is to reflect on how these decisions were made and wrote them down as a strategy.

- Analyze and Synthesize Design Documents - Review the five design documents collectively. Identify and focus on controversial or difficult decisions that recur in multiple documents. Use these insights to form a cohesive strategy.

- Guide Tradeoffs with Clear Rationale - Effective strategies should guide decision-making tradeoffs and clearly explain the underlying rationale. Avoid strategies that state policies without context, as they quickly become irrelevant and difficult to adapt.

- Be Specific and Opinionated - Emphasize specifics in your strategy, avoiding generalizations. Strategies should be opinionated, providing clear guidance on decision-making, and must demonstrate the thought process behind these opinions.

- Show Your Work - Like solving a math problem, showing your work in strategy development is crucial. This approach not only builds confidence in the strategy but also allows others to understand and adapt it as contexts change.

Combining Strategies into a Vision

Creating a compelling engineering vision from multiple strategies involves weaving together different approaches into a cohesive plan for the next two to three years. The final version should give you what Tanya Reilly calls "a robust belief in the future - the result should be a common thread among existing strategies as well as making it easier to write additional strategies that stand the test of time. Here's a few tips for writing a vision:

- Combine Strategies Thoughtfully - Analyze and harmonize different strategies, even if they seem contradictory.

- Focus on a 2-3 Year Horizon - Develop a vision that is realistic for a rapidly changing technological and business landscape.

- Align with Business and User Needs - Ensure the vision serves users and aligns with leadership's core values. (Ineffective visions may overemphasize technical complexity without clear benefits to customers or alignment with leadership values. For example, a vision that proposes using the latest AI technology because it's innovative, without showing how it drives business growth)

- Be Ambitious but Realistic - Aim for the best possible outcomes within resource constraints. (You're not writing a vision with the assumption of infinite resources)

- Detail Matters - Provide concrete details and avoid vague statements to guide strategy effectively.

- Keep It Concise - Limit the vision to 1-2 pages and link to more in-depth documents for interested readers. (Most people won't read longer than a page)

- Share and Refine - Share across the organization and measure success by the improvement in strategies and design documents over time.

Managing Technical Quality

One of the roles of engineering leadership is to maintain appropriate technical quality, while still devoting as much energy as possible to the core business. It's easy to point fingers when technical quality is low, but this scenario is not a crisis - it's expected. Some tips the books recommends:

-

Start with the lightest weight solutions first - only progress toward massive solutions as earlier efforts fail to scale. Quick fixes provide valuable learning experiences. Celebrate the removal of ineffective practices along the way.

-

Adopt a performance engineer mindset to identify hotspots - When facing quality issues, it's tempting to pinpoint and rectify process failures (i.e, we had a deployment cause an outage because a code author didn't correctly follow a code test process, so let's require tests with every commit). It's more important to identify the actual problem and hand than to implement fixes via process-driven accountability. Teams should adopt a

performance engineer's mindsetwhereby they measure the system, identifying where the bulk of issues lie so you can focus on just that area. - Sometimes it's also better to just discard an issue rather than try to fix it -

Align technical decisions with shared visions - ensure you avoid centralizing decisions with one architect, and instead, use tools, onboarding and organizationl design to foster alignment

-

Gradual best practice implementation - Successful adoption of best practices, like Scrum, requires a gradual approach, starting with small tests and evolving based on feedback. It's important to focus on one practice at a time, ensuring each is well-established before introducing new practices, and to base the adoption on solid research and readiness.

-

Targeting leverage points - identifying hotspots works well for issues you already have, but there are a small subset of areas where extra investments preserves quality over time (

"leverage points). Areas of concentration should be interfaces (mediators between different parts of software that hide complexity), stateful systems (an area that gets complex faster than any other area), and data models (at the intersection of stateful systems and interfaces, and should be designed to be rigid yet still flexible to changes over time) -

Aligning technical efforts with org vision - all technical decisions should support a unified vision (like vectors pointing in the same direction). To prevent misalignment, the book recommends several strategies including direct feedback, training and feedback, leverage Conway's Law where orgs create systems that reflect their structure, and developing engineering strategy based on tech specs that also reflect the broader org strategy/vision.

Measuring and Enhancing Technical Quality

Accurate measurement of technical quality in software engineering is key. It's crucial to have a good definition of quality - and then to have the instrumentation to create a quality score that you can track over time.

Some technical quality definitions might include:

What percentage of the code is statically types?What percentage of files use the preferred HTTP library?Do endpoints respond to requests within 500ms after a cold start?How many functions have dangerous read-after-write behavior?

Technical Quality Team

Establishing a technical quality team (sometimes called Developer Productivity, Developer Tools, or Product Infrastructure) dedicated to improving and preserving software quality across the company is crucial. This team should focus on measurable impacts, user-centric tool design, and prioritizing high-impact projects.

Some tips for the success of quality teams:

- trust metrics over intuition

- adoption/usability of your tools are much more important than raw power - so do user research on your tools and listen to/learn from your users

- do fewer things, but do them better

- avoid having the quality team impose a globally optimal or one-size-fits-all approach for all teams (i.e, some teams have atypical workloads - think developers using a Javascript backend, which doesn't mesh well with a Machine Learning team that wants everything to be in Python). Understand each team's unique requirements and find a healthy balance between standardization and accommodating diverse needs

Staying Aligned with Authority

To be effective within a staff-plus role, you'll need to retain some level of organizational authority, which depends on remaining deeply aligned with a bestowing sponsor - generally your direct manager. Typically, the support system that got you to a staff role will fade away when you're there, so you must align the pieces around you for your own success.

The book highlights several tips for strategic alignment:

-

Communication is key - try to prevent both you surprising your manager and your manager/sponsor surprising you through frequent and open lines of communication.

-

Feedback and adaptation - regular feedback and a willingness to adapt are important

- Proactively solve problems by signaling to your manager - To prevent your manager from getting surprised by the organizations, considering feeding them additional context of problems you're noticing

-

Aligning vision with leadership to influence effectively - You should develop your own perspective on how the world should work (this sharpens your judgement and proactive capabilities). However, make sure to align your vision with that of senior org leaders, while still maintaining some sense of your own ideas in a non-confrontational way - this will let you influence without friction.

Lead by following

Management is a profession, but leadership is a trait one can demonstrate within any profession. The most effective leaders spend more time following than they do leading:

- They give support quickly to others who are working to make improvements

- They make feedback explicitly non-blocking if there will be disagreements (share perspective rather than suggesting people change their approach)

- They integrate their worldview with their team's, thereby accelerating progress

- They define the gap between how things are and how they ought to be, and identify proactive solutions to narrow the gap. They also care enough about the gap to attempt solutions.

Agreeing on Decisions

I present what I think is the best case for us, and people can disagree with that. And, you know, they often do. I’m steering and influencing more than saying, “I’ve got the authority to just tell you what to do.” I’ve never seen that style work well. - Keavy McMinn

- Effective meeting strategies -

- Approach meetings with the intent to understand and align with others, rather than just pushing your own perspective

- Listen through questions - this involves active listening and asking questions to understand other's viewpoints. **Ask 3 good questions before you share your perspective ** (you'll likely see the room shift)

- Defining a clear goal/purpose for meetings

- Read the room to understand when to escalate discussions or break them down into smaller groups

- Avoid forcing consensus in meetings - identify ways to explore disagreements

Often, engineers are confident their perspective is right, so there are ocassions where getting other folks in the room to agree is sometimes a zero sum game. Instead, think about applying some of the approaches listed above and think about entering a room with the goal of agreeing on a problem at hand.

Difficult Colleagues

The above approaches work well for leaders looking to reach agreement with the majority of folks - but you won't agree with everyone. Difficult colleagues will often withold consent from the group or don't really listen. Some possible strategies to handle this include:

- Including folks in a meeting that the difficult colleague can't be rude to (like a VP of Engineering)

- Aligning with them before the meeting, so they feel heard and are less likely to derail the discussion

Creating space for others

At this point, I spend less time advocating for specific technologies or programs and more time empowering others to advocate for the technologies and programs that they think are important. I also try to be a source of knowledge and support that people can reach out to for feedback, especially on cross-cutting product decisions and on presentation of ideas to the rest of the organization. - Michelle Bu

One indication of a successful staff-plus engineer is that your organization benefits from your contributions, but doesn't rely upon them. Many staff-plus reach the role by becoming the "go-to" person for their organization, so it can be difficult to transition from essential to adjacent.

-

Create more space for others in discussions:

- When you make a key contribution, reflect on what it would take for someone else to make that contribution next time

- Shift contribution toward asking questions

- Think about trying to involve folks who may not be participating

- Destigmatize low status activities like note-taking

-

Help others learn from decisions:

- Record decisions (write them down) so that others can learn

- Circulate decisions early (and before you've crystallized on a decision)

- Being able to listen to coworkers and being open enough to change your mind based on different discussions

-

Creating space via sponsorship

- When you get critical work, ask yourself who could grow the most by taking on this work - then have them lead that task/project

- As a sponsor, you can advise and provide context, but ultimately you should be able to let the person you're sponsoring take an approach that you wouldn't

The only way to remain a long-term leader of a successful company is to continually create space for others to take recognition and reward.

Building a Network of Peers

Of the staff-plus engineers interviewed in the book, the most consistent recommendation was to develop a network of peers.

- Be visible - Since there is a pent-up demand for community among staff-plus eng, the easiest way to build a network is to be visible (conferences, staff eng slack spaces)

- Internal networks - This is easier at larger companies. When folks leave your org and spread across the industry, it will help bootstrap your broader network

- Quality over quantity - Build your network with folks you trust, respect, and who inspire you. They'll help you solve the most difficult problems that come your way

Presenting to executives

Your career is constrained by your ability to influence executives effectively. This is a skill on its own, since executives are usually unfamiliar with your domain and have limited time for the topic at hand. Presenting to executives can be challenging if your presentation style does not align with what executives are accustomed to, particularly if it leads to the conversation being derailed. For example, some executives might focus solely on data, discounting any points not directly tied to concrete evidence.

Preparing in advance to align your presentation with styles can help prevent miscommunication and increase the likelihood your ideas will be received positively. When you meet with executives it's typically for planning, status reporting, or resolving misalignment. The key objective is to gain as much insight as possible from the executive, rather than trying to change their mind.

-

Structured documents are a key tool to help clarify your thoughts. One such format is SQCA:

- Situation - define relevant context

- Complication - explain why current situation is problematic

- Question - state core questions to address

- Answer - state best answer to posed question

-

Mistakes to avoid:

- Never fight feedback - if you do, others will withhold comments and you'll get less out of it

- Don't evade responsibility/problems - by putting issues on the table, you can move towards solving together rather than trying to hide things

- Don't present a question without an answer - doing so may make executives question judgement

- Don't fixate on a preferred outcome - there could be context you're missing

Promotion Packets

Creating a promotion packet for a staff-plus role can be a strategic tool for career development. Instead of viewing it as just a requirement for promotion, it can serve as a roadmap for reaching your goals

-

Start early - begin working on your staff promotion packet well before you're up for promotion - using it as a guide rather than just a formality

-

Template for packet - include details of your staff projects, organizational improvements you've contributed to, the quantifiable impacts of your projects, mentorship roles, "glue work" for the organization, and areas for personal improvement

-

Iterative Process:

- Personal reflection - understand why you want a Staff level position and ensure it aligns with career aspirations

- Manage expectations - recognize that promotions at this level take time (promotions built over years)

- Engage your manager - discuss your promotion goals and the packet in your one-on-ones, seeking feedback and guidance

- Regularly discuss your progress towards meeting the promotion with your manager (addressing any gaps so as to strengthen your case)

- Write and Revise - initially draft your promotion packet, then review and edit it for clarity/content

- Get feedback from peers (especially those in staff-plus roles)

-

Find a sponsor - promotions are a team activity - don't play team games alone. This should be a person speaking up for your work in forums of influence.Sponsors typically possess considerable organizational capital but limited time, so you must assist in aligning the pieces for them.

-

Make sure your skip-level manager is familiar with your work's impact to remember it in a meeting

This approach is not just about assembling a packet for promotion; it's about focusing your efforts and aligning with your manager to actively work towards your goal. When it's time to formalize your packet, it will be a refinement of your ongoing work rather than a last-minute compilation, making the promotion process smoother and more reflective of your continuous development.

Staff Projects

There isn’t an explicit expectation, nor is it listed anywhere as a formal requirement, but it is understood that you’ll complete a Staff Project to get promoted. I can’t think of any Staff promotion that didn’t include a really strong project, typically a multi-person project where the engineer was the Tech Lead. - Ritu Vincent

Most individuals who attain a staff role do so by either accumulating a solid track record over time, switching roles to attain the title, or completing a "staff project". The staff project is usually complex and important enough that the person who copletes it has proven themselves a Staff engineer. Some of the characteristics of a staff project include:

- Complex/ambiguous - In contrast to early career (well-defined) problems, the staff project is large, ambiguous, and poorly scoped. Part of the challenge is working through this ambiguity

- Numerous and divided stakeholders - a lack of organizational alignment around the problem and its solution

- Highly visible - talked about at "All Hands" type meetings. As a result both failure or success will be visible.

In order to obtain access to projects of this nature - the book offers a few additional tips that includes:

- Stay highly aligned with leadership team

- Be known to have technical aptitude for the problem at hand

- It helps when your company has a pressing need to solve a staff-level problem

Regardless of whether or not you want the staff title - you should still pursue self-growth opportunities that staff projects provide

Get in the decisioning room, and stay there

Gaining access to key decision-making spaces, often referred to as "the room," is a common challenge and aspiration for engineers, especially at the Staff-plus level. Here's a succinct summary of the advice provided:

-

Bring unique value - have something useful to contribute that isn't already present

-

Find a sponsor - secure someone in the room who will advocate for your inclusion. Also make sure to communicate to sponsors that you actually want to be in the room

-

Volunteer for tasks, even if they're low-status - i.e, note-taking

-

Understand the room's purpose - align with the room's intent and operate within its norms

-

Be low friction - you're more likely to be involved if you're known as someone who can navigate difficult conversations effectively

-

Be consistent - regular attendance and reliability are crucial

-

Speak clearly and concisely - learn to use economy of speech. It's your responsibility to be understood

-

Exiting the room:

- Evaluate the room's value - assess whether the room is a beneficial investment of your time

- Leave Strategically - If a room no longer serves your goals, consider exiting and potentially sponsor someone else to take your place

Being Visible

Your goal is to be known for good things while minimizing org bandwidth you consume to do so. Staff-plus roles are leadership roles - and by giving you such a title, the company is bringing you into its leadership team. In order to bring you into leadership, existing leaders have to know and believe in you.

-

Internal Visibility - work on things that matter to your leadership and org. A good reputation and visibility within the company are crucial to promotion to staff. Produce and share long lasting documents like architecture docs or tech specs. Lead or participate in company forums and events. Promote your team's work and achievements on Slack/email.

-

Executive Visibility - It's particularly important to be known and trusted by the company's executives (as they have a say in promotions). Building a relationship with your skip level manager can be valuable here.

-

External Visibility - This could be a conference talk or a highly publicized blog. While with internal efforts, your competing for attention with your peers, external efforts don't have this same competition.

Conclusion

The 'Staff Engineer' book is a personal guide for engineers navigating their journey towards Staff and Staff-plus roles in the tech industry. It's like a mentor in print, providing valuable insights into career progression, leadership, and the art of effective communication. The book not only outlines the paths to success and the essential skills required but also inspires with its focus on the personal significance of visibility, strategic decision-making, and aligning one's values with organizational goals. It's a hopeful beacon for aspiring engineers, encouraging them to balance technical prowess with strategic thinking and interpersonal skills to reach new professional heights.