1️⃣ Part 1: Supervised Learning and Neural Networks

3️⃣ (Coming soon)

4️⃣ (Coming soon)

Introduction

Randomized Optimization (RO) is a powerful alternative when traditional gradient-based methods fall short — especially when the fitness function is not differentiable or the search space is rugged and full of local optima. In this project, I explored four classic RO algorithms — Random Hill Climbing, Simulated Annealing, Genetic Algorithms, and MIMIC — applied to two challenges:

- Tuning neural network weights

- Solving three well-known optimization problems: Continuous Peaks, Flip Flop, and the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

Part 1: Neural Network Weight Tuning

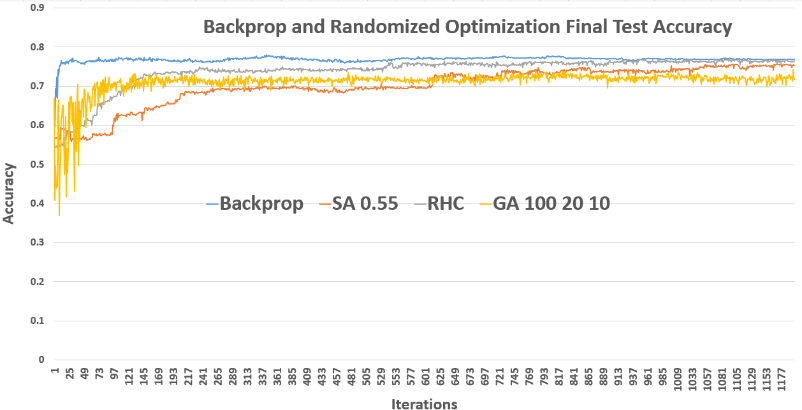

Before tackling standalone optimization problems, I tested how well RO can tune neural network weights compared to traditional backpropagation with gradient descent.

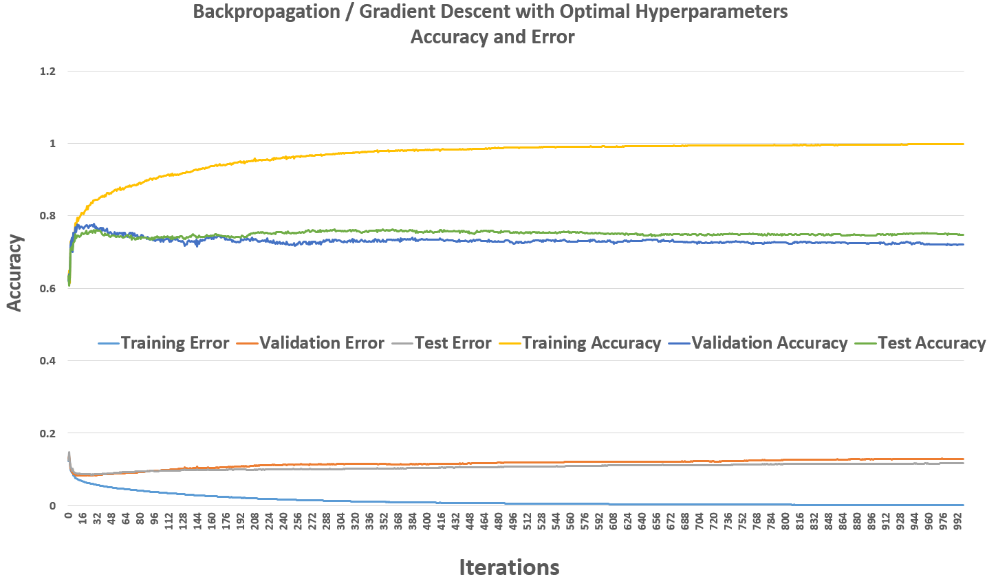

Backpropagation / Gradient Descent

As a baseline, I trained a neural network with three hidden layers of 22 nodes each using backpropagation. This classic method computes the gradient of the cost function and updates weights accordingly. As expected, the training error converged quickly within 100–200 iterations, with test accuracy stabilizing around 76%.

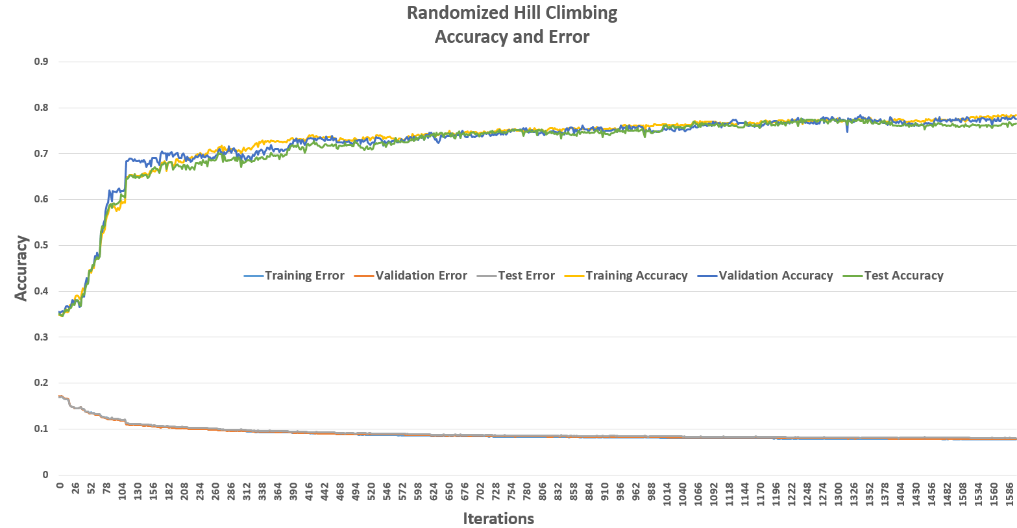

Random Hill Climbing (RHC)

RHC starts with a random guess for weights and iteratively tweaks them to find better configurations. To avoid getting stuck in local optima, I used random restarts. Despite this, RHC required about 1000 iterations to converge — much longer than backpropagation — highlighting the challenge of small attraction basins.

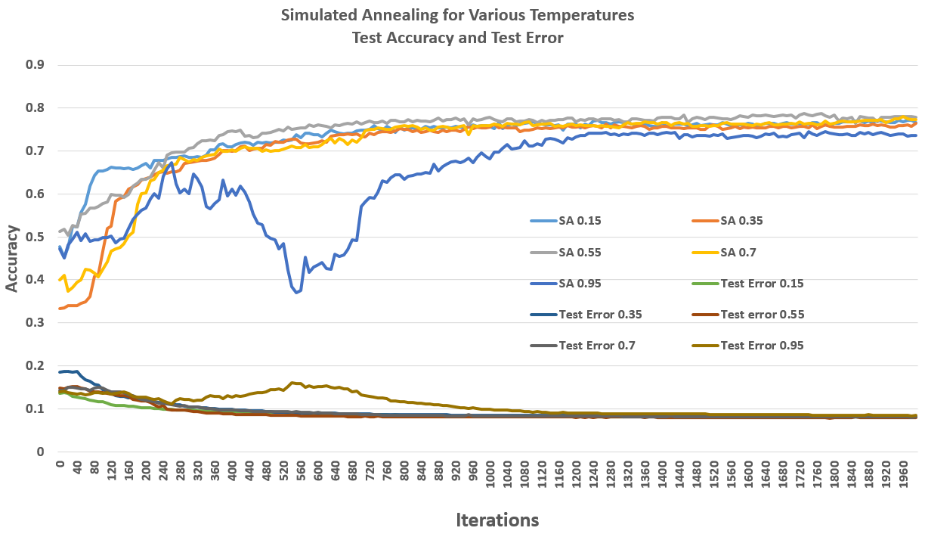

Simulated Annealing (SA)

Simulated Annealing is inspired by metallurgy: it allows occasional downhill steps to escape local optima, controlled by a temperature parameter. I tested different cooling rates and observed that higher rates (slow cooling) sometimes led the network to wander into higher-error regions. Overall, SA showed reliable convergence but required careful tuning to balance exploration and exploitation.

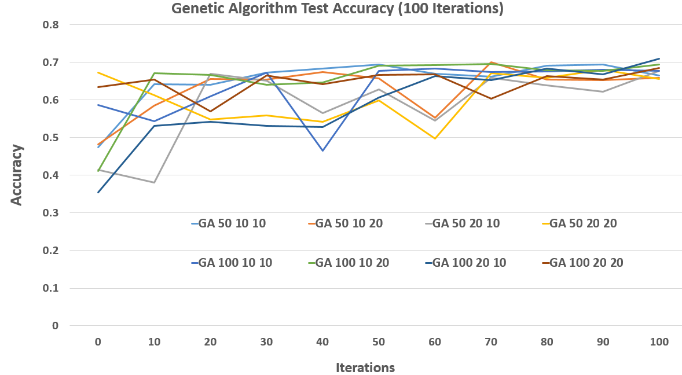

Genetic Algorithm (GA)

The GA treats weight configurations as "individuals" in a population. It evolves them over generations using selection, crossover, and mutation. I varied population sizes and mate/mutation pairs, finding that larger populations boost diversity and performance but also increase runtime. GA often showed more volatile convergence due to its exploratory nature.

Part 1 Comparison

Overall, backpropagation remains the fastest and most reliable for weight tuning. Among the RO methods, RHC and SA converged faster than GA, but all lagged behind gradient descent in both time and final accuracy.

Part 2: Solving Classic Optimization Problems

Next, I applied all four RO algorithms to three classic optimization problems: Continuous Peaks, Flip Flop, and the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP).

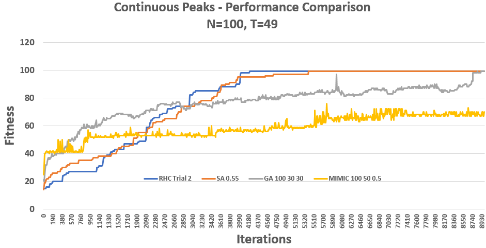

Continuous Peaks

Problem: Maximize the reward for having long contiguous sequences of 0s or 1s in a bit string, with an extra bonus if both exceed a threshold.

Key observations:

- RHC: Multiple restarts helped cover the search space but convergence varied by trial.

- SA: Best results with moderate cooling rates; high rates wandered too much.

- GA: Showed oscillating fitness but steadily improved.

- MIMIC: Captured problem structure well for smaller instances but required more computation for larger N.

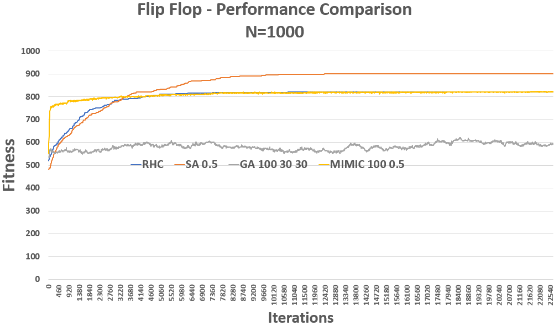

Flip Flop

Problem: Maximize the number of alternating bits in a bit string (e.g., 010101...).

RHC and SA reliably climbed to high fitness. GA fluctuated near convergence due to crossover mutations. MIMIC needed many evaluations and didn’t outperform SA here but showed promise with more tuning.

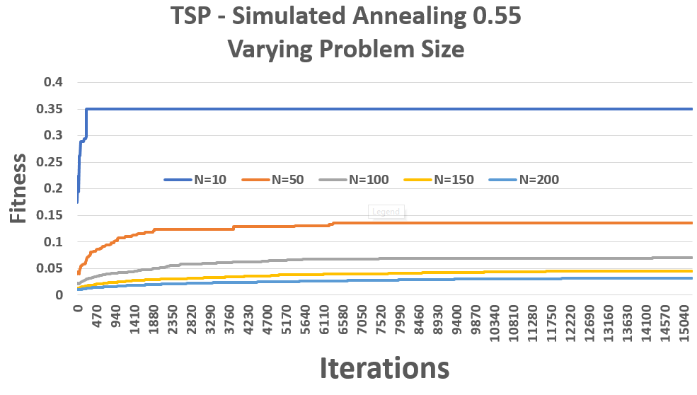

Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

Problem: Find the shortest path visiting each "city" exactly once and returning to the start.

Given its NP-hard nature, TSP challenged all algorithms:

- RHC & SA: Got stuck in local optima more often due to the huge combinatorial space.

- GA: Outperformed the others by maintaining a diverse population of routes.

- MIMIC: Surprisingly underperformed, likely due to parameter settings and the complexity of modeling dependencies in valid paths.

Conclusion

This exploration shows that while backpropagation remains the best tool for neural network weight tuning, Randomized Optimization shines for rugged, non-differentiable problems — as long as you pick the right algorithm and tune it carefully.

Optimization Problems Summary

| Problem | Algorithm (parameters) | Converged Fitness Score | Iterations to Convergence | Function Evaluations to Convergence | Elapsed Time at 1000 Iterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Peaks N=100 | Simulated Annealing (0.55) | 100 | 5,500 | 5,000 | 0.002047 |

| Genetic Algorithm (100 30 30) | 100 | 8,500 | 500,000 | 0.187553933 | |

| MIMIC (100 0.5) | 100 | 7,500 | 1,000,000 | 6.268513083 | |

| Flip Flop N=1000 | Simulated Annealing (0.55) | 900 | 10,000 | 10,000 | 0.022018 |

| Genetic Algorithm (100 30 30) | 580 | 1,500 | 570 | 1.772045639 | |

| MIMIC (100 0.5) | 800 | 8,000 | 1,000,000 | 254.5714739 | |

| Traveling Salesman N=100 | Simulated Annealing (0.55) | 0.08 | 43,000 | 50,000 | 0.002047 |

| Genetic Algorithm (100 30 30) | 0.1 | 1,000 | 15,000 | 0.187553933 | |

| MIMIC (100 50 0.5) | 0.022 | 100 | 6,500 | 254.5714739 |

No single method dominates all tasks:

- MIMIC can capture structure but is computationally heavy.

- GA balances exploration and diversity but can be volatile.

- SA is reliable if well-tuned.

- RHC is simple and effective but easily stuck.

Future improvements could include a more exhaustive hyperparameter grid search, trying hybrid methods that blend gradient descent and RO, or applying these techniques to larger, real-world problems.